The Beginning 1990

Grabbing my bags, I tread softly down the hall, passing the hushed rooms of sleeping patients, chirping monitors and the light banter at the nurses’ station. Someone moans. I don’t say goodbye because I am becoming more and more like my mother, who abstained entirely from any parting etiquette. But she also used to eat her lunch in a bathroom stall, so I’m aware there’s balance.

The clock reads 2332, military time for 11:32 pm. I grab my badge from my waist and reach for the time punch clock, sliding it downward until I hear the beep, signifying I will be paid. Done. And with that very ordinary transaction, a career spanning over 30 years at Cape Cod Hospital was over.

I found the stairs and grabbing the rail, I hobble down the steps, my right knee complaining the whole time. Smiling, I see a much younger Me bounding up the same staircase in the early 90’s, two steps at a time. I think I was in my tie-dye t-shirt paired with pink socks phase. Scrubs had just been liberated from all whites to colors. Smoking was banned from the nurses’ stations but not the breakrooms, and the cafeteria had a dense layer of smoke hovering just above the tables. AIDS was the new pandemic. Bruce, the only pharmacist, parked outside the cafeteria at a window that looked like he was selling train tickets, and if a nurse had cramps or a headache, he would bounce a couple of Tylenol across the counter.

The halls are quiet. I pass a lab tech pushing her cart, head bent to her phone. We nod. Most of the people that I knew well, that I had shared tears and laughter and the grit of human brokenness with are gone. Those remaining, whom I saw within the last week, knew I was leaving. We embraced, years in the trenches of med surg, critical care and ER, passing between us.

The halls are quiet. I pass a lab tech pushing her cart, head bent to her phone. We nod. Most of the people that I knew well, that I had shared tears and laughter and the grit of human brokenness with are gone. Those remaining, whom I saw within the last week, knew I was leaving. We embraced, years in the trenches of med surg, critical care and ER, passing between us.

It’s Saturday night. As I walk towards the ER my mind remembers and flips through the usual casualties – fights and brawls and falls. The psyche section shrouded in despair, stretchers tucked away behind TV sets. We have no answers, I wanted to say. The old man, wearing golf shoes, sobbing over his lifeless son, My baby, my baby. The bewildered parents dropping off their ten-year-old child. We can’t control him. The woman in a wheelchair being whisked to maternity, holding a “burrito,” a brand new human wrapped in a shiny heating blanket, her face flushed with messy joy.

I became a nurse at age 33. I was still awkwardly optimistic, gazing into the glorious face of Jesus, believing hard that I had become a new creation, with traces of leftover skeptic. The first thought of being a nurse occurred years before, in the dark, when I would drink a “Cocktail for Two” on my way to night school, and the algebra teacher would lean close to my blurry face, his eyebrows arched in helpless compassion. I thought he just cared about my math disability but now I’m sure it was deeper. I got sober the next year, then two years later crashed into Jesus. It was a setup.

I became a nurse at age 33. I was still awkwardly optimistic, gazing into the glorious face of Jesus, believing hard that I had become a new creation, with traces of leftover skeptic. The first thought of being a nurse occurred years before, in the dark, when I would drink a “Cocktail for Two” on my way to night school, and the algebra teacher would lean close to my blurry face, his eyebrows arched in helpless compassion. I thought he just cared about my math disability but now I’m sure it was deeper. I got sober the next year, then two years later crashed into Jesus. It was a setup.

At some point, nursing became a call, not a career. If it was a career, my warbly timeline would appear to be a disaster. Calling is Spirit-vision, the unseen things, and holding the hand of God in the dark. You will not be afraid. His peace, His love and patience will keep you while the world around you collapses in sickness and suffering. And then, if you focus, He pours through you, bringing His light and healing. Sometimes you save a life. Sometimes it’s a prayer at the end of it. And sometimes it’s just a cold ginger ale.

My favorite shift – working with my son Jake 2022

Somewhere upstairs a wet, squinty newborn wails for the loss of the womb, and right below, a last breath escapes into the colorless night. God is not surprised by any of this. He weeps, He rejoices. He whispers, Let me in!

I can’t count the bodies I’ve washed and pushed and pulled and rolled. How early on I learned that the most valuable nursing skill, way ahead of IV sticks and NG tube drops and foley insertions is prayer. Then touch.

Jesus reached out his hand and touched him. My hand, holding another hand, or resting on an arm, a forehead. It may not heal but it boosts the chances in an unimaginable way.

I think nursing is an ancient craft. It is filled with touch and light and pain and exhaustion. Dark humor helps. And here is where we must guard our hearts. When humor turns to cynicism and contempt encases your heart, you will become more harmful than Healer. You can click through your shift, checking boxes, dodging arrows, your mental task board being shuffled and reshuffled ten times with Keep patient alive hopefully looming near the top, but go home feeling empty and disconnected. And the wine that you thought of all day won’t help one bit.

So six tips from an old nurse:

So six tips from an old nurse:

- Learn to laugh. If nothing is funny, be funny. My last week, donning a yellow isolation gown, another nurse and I created an impromptu “Dance of the Daffodils.” It was a big hit.

- Learn to listen. A priceless gift.

- Learn patience. Sick people move slower than an Alaskan glacier.

- Learn to weep. For the wife saying goodbye to her husband of 65 years. For your traumatized coworker. For the stupidity of the human race. Let your heart break, then let Jesus put His hand on it.

- Learn to pray. God hears and is there. I can’t imagine doing this job without Him.

- Learn to leave. Change is good. Old nurses never die. It’s too much paperwork.

Nurses are like Marines in this way. It’s in us. I can spot a smoker, an alcoholic, a heart–liver–or kidney failure, a looming hypertensive crisis, or a heart attack. And I don’t even mind looking at your kid’s bump or your rash, but I’m known to be rude and dismissive. Ask my own kids. “You’re fine, go out and play.”

Nurses are like Marines in this way. It’s in us. I can spot a smoker, an alcoholic, a heart–liver–or kidney failure, a looming hypertensive crisis, or a heart attack. And I don’t even mind looking at your kid’s bump or your rash, but I’m known to be rude and dismissive. Ask my own kids. “You’re fine, go out and play.”

I climb a short set of stairs before pushing open the heavy metal door, grabbing the rail again. The night air is damp and salty, and the door closes with a hush. There is no one. I look up at the darkened offices in the old section of the hospital, where I first began as a new nurse, full of terror and bravado, then glance over to the ER entrance. An ambulance chugs rhythmically in the tunnel. A dozen possibilities flip through my mind, heavy and sad. Things you won’t read in the paper. Nurses carry lots of stories stuffed in a secret file.

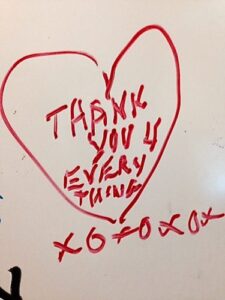

I turn into the wind towards the parking lot. A young nurse walks hurriedly under the street lamp and I wonder how her shift was, if she feels like quitting or wishing she could do something else, like flower arranging or Dunkin’ Donuts. Or maybe she had one of those magical moments when a patient says, “Thank you, you helped me,” and all the schoolbooks and fear and panic and filthy scrubs and unmentionable clean-ups become so worth it.

I turn into the wind towards the parking lot. A young nurse walks hurriedly under the street lamp and I wonder how her shift was, if she feels like quitting or wishing she could do something else, like flower arranging or Dunkin’ Donuts. Or maybe she had one of those magical moments when a patient says, “Thank you, you helped me,” and all the schoolbooks and fear and panic and filthy scrubs and unmentionable clean-ups become so worth it.

You go home, shower and fall into a fitful rest because your body is so crushed and spent, but your mind has a 1200 volt current buzzing through it. Did I recheck that blood pressure? 02 Sat? Check labs, orders, EKGs? Then, the guilt, knowing that patients deserve more than one stretched and wrung-out nurse can ever give. Alarms echo in the recesses of your mind as you drift into a turbulent sleep, awakened by another alarm. Get up and do it again.

I pull out of the parking lot, not looking back and a sweet other-worldly peace settles in my soul. Well done? Within the confines of my human frailty and vast shortcomings, within the immeasurable grace and patience of an Almighty God, it was enough.

I slept soundly that night. Semper Fi.

Penned by a grateful patient