Big Sid must be dead now. I was a teenager when we first met and he seemed old. My parent’s age anyway. Like forties? He was big. I see him flopped into and filling an even bigger chair, his sleeves rolled up above his thick meaty hands. A white collared shirt billowed around his waist and tufts of untamed brown hair framed his jowly face. But the eyes! That’s what you never forget. Sad but playful, always alert – droopy eyes that saddle-bagged a long slender Jewish nose, and eyebrows that hoped to laugh. Child eyes that searched yours, looking for a sign, to see if you got it.

Sid was a New Yorker through and through, shrugging at tragedy. What can you do? But he saw people the way they were meant to be, the rough draft. In the new world of pop psychology and the “I’m Okay/ You’re Okay” doctrine of the early ’70s, he sat apart. Crazy was okay in Sid’s playbook. Not just okay, but pretty cool.

I heard Big Sid stories for a while before we met. He was my mother’s therapist, and her eyes danced with joy when she spoke of him. Joy was rare back then, so I was intrigued. I had already run through a hodge-podge of therapists, counselors and one bald psychiatrist who would sleep while I talked. At first, I thought he was ruminating on my words, transforming my jumbled psyche into a completed puzzle, like a Rubrics cube, his eyes closed in transcendent thought. But one evening he snored, and I stopped talking, waiting for him to awaken. When he didn’t, I escaped on tiptoe.

I was 14 when I met Big Sid. I’m not one hundred percent sure of this, but I was old enough to be troubled and cynical but still hadn’t left home for good at 15. With tangled long hair, clothed in anything that evoked shock and projected rebellion, I was good at intimidation. Once I took an hour-long commuter train ride home from New York City during rush hour and challenged myself to see if I could keep the seat beside me empty just by projecting attitude and anger. I won.

But Sid disarmed me. Immediately. It was like he looked right past me, the rage and belligerence to a little girl that chose pirates over princesses, that would never sit still in a classroom, and who became confused and withdrawn around meanness. He neither blamed me nor excused me for becoming who I was, nor did he think he could fix me. Behind the sad eyes and the earthy Jewish New York accent, he cajoled the real Robin to come out of hiding. What I didn’t expect was for him to enjoy what he saw.

This search for self and meaning was nothing new, but Freud and Jung heralded in a new preoccupation with self-dissection. My mother was all in. It bothered her deeply that she could make absolutely no sense of her life or the children she bore. The navel-gazing 70s only heightened introspection, birthing more therapies, and the peddling of legal drugs. I was drowning, and the lifeline was one diagnosis layered over the next. Manic-depressive (the modern-day Bipolar), clinical depression, passive suicidal, alcoholic. At age 20 I was locked away. Strangely, the click and turn of the lock was comforting. I just wasn’t getting it. Life.

When I got out, I looked for Big Sid. My grandfather, a physician, funneled a huge amount of cash into my mental well-being, mainly because he felt bad for my mom, having to deal with so much lunacy. Now I was 20, on five medications, and running from my shadow. Sid looked the same, spilling over the chair, the shabby paneled office that smelled of ashtrays and whatever Sid ate for lunch. He seemed quieter this time. Now I think he must’ve been shocked by what he saw. I remember my hands shaking, that feeding myself was difficult.

When I got out, I looked for Big Sid. My grandfather, a physician, funneled a huge amount of cash into my mental well-being, mainly because he felt bad for my mom, having to deal with so much lunacy. Now I was 20, on five medications, and running from my shadow. Sid looked the same, spilling over the chair, the shabby paneled office that smelled of ashtrays and whatever Sid ate for lunch. He seemed quieter this time. Now I think he must’ve been shocked by what he saw. I remember my hands shaking, that feeding myself was difficult.

“You’re too young to be on medication,” he said softly. “It will take a year, but I’m going to wean you off all of these meds.”

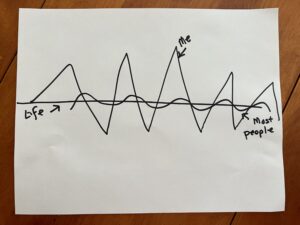

He leaned forward, grabbing a blank sheet of paper and pen from his desk. His thick hands drew a line across the middle. Then he slid it closer to me.

“You see this line, Robin?” I nodded. “That’s life.” Then he drew another line that moved smoothly through the first line, creating a slight ripple over the top and bottom of it, a gentle wave.

“This is how most people are,” he said as he finished and gave me time to look. “Boring,” he muttered. “Now this is you.”

A copy of the original😊

He grabbed the paper and worked a new line through the straight one, but this line was a zig-zag, with uneven high peaks coursing way above and below the line in no real order.

“That’s who you are. That’s how you were made.” His beautiful eyes searched mine. “And it’s okay. You just have to learn how to be you.”

I kept that paper tucked into my heart until I met Jesus some ten years later. I knew I was different, but I was still mad and scary. I rode out the deep lows and the too highs like a cowgirl, but I was tired. How could you not be, living a life that always boomeranged back to you? Then in a moment, God fixed it. He did what Sid knew he could not – what no therapist or medication could do, but He had to wait until I was ready to give Him everything. All the rage and bitterness intertwined like kudzu, deep within the primal jungle of a broken soul – places no man can see or reach, the roots gnarled and woven tightly through generations of uncovered darkness. There He brought light. Then it was gone – just like that. I was free.

I still squirm in a classroom. And some days I have so many bright ideas, I have to lie down before I fly apart. Then other days are just sad. Melancholy rolls in like a cool offshore fog, and I am unsettled and wistful. So I take walks or bake something. Jesus is right there, and not without compassion.

I still squirm in a classroom. And some days I have so many bright ideas, I have to lie down before I fly apart. Then other days are just sad. Melancholy rolls in like a cool offshore fog, and I am unsettled and wistful. So I take walks or bake something. Jesus is right there, and not without compassion.

I’m sure Big Sid is long gone now. But I will never forget the sad eyes that really saw me and the simple lines across a blank page. Thank you, Sid. You couldn’t fix it, but you gave me the legs to run and a little bit of hope that I could get there. Even Jesus thinks crazy is cool. After all, He made me.

I will praise You, for I am fearfully and wonderfully made;

Marvelous are Your works,

And that my soul knows very well. Psalm 139:14

Still unmedicated, but safe to sit next to now.