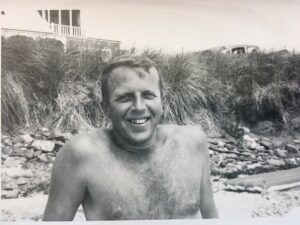

My dad —circa 1962

*** Dear friends- in the beautiful but sometimes perplexing spirit of Father’s Day, I am reposting this from 2017. I pray it will bless and minister to someone!

Pawwwwwt Chestah!!

I can still hear the conductor holler over the clack and rattle of the train and the steady kachuk kachuk kachuk of the wheels on the rails. Port Chester, Rye, Harrison. Back then, in the 60’s, it wasn’t an odd thing for a little girl to ride the train alone. The conductors that strode like drunk men up and down the swaying cars knew my dad, knew that he worked in New York City like most men from Riverside, Connecticut and that he would be there, at Grand Central Station, watching for the wave of the conductor as he would signal me to go.

“There he is!” they would call out, as I ran from the train to my father.

New Rochelle! These places didn’t look much different to me until we reached Harlem.

“One hundred and twenty fifth Street!” I learned that was the final call before the last stop. The station was filled with people that were strange to me, dark-skinned with ragged clothes. But it was more than the way they looked, or didn’t look. They moved slower, like they had no where to get to, like trains and time didn’t matter much, not like my town, where men in crisp suits and new briefcases often ran to catch the train.

The seats were soft blue velvet and smelled like my dad, cigarettes and shaving cream. I liked to pull up the window so I could feel the air rush in and hear the tracks beat out their rhythm…kachuk, kachuk, faster and faster as we pulled away from each station. I could smell the air change as we pressed forward, farther and farther from the salt air of Long Island Sound and the heavy perfume of tall maple and elm trees, into the colorless exhaust of Harlem. It was different in so many ways.

My father took me to Radio City Music Hall several times — Nutcracker Suite, the Rockettes — all the things he knew a girl would love. I remember gawking at the bare legs flying up in the air in unison, because these women must be the “chorus girls” my mother made reference to when I behaved in a coarse way, like belching or chewing gum. But what I loved the best was going to his office, high above Manhattan, being “Bob’s little girl” and the pride he showed as he smiled down at me while people filtered through. I knew that I, his big desk and the view over New York City, made him feel special, like he did something right, and I loved sharing that moment.

Our Father who art in heaven, hallowed be thy name.

I never thought of this Father too much growing up, the one in church. For one, heaven seemed very far away, so this Father must be too. My sister thought they were saying, Harold be thy name instead of Hallowed which made more sense because we had an Uncle Harold. Who ever heard of someone named Hallowed? Anyway, I had a father, right here and he was the daddy of the big desk and the Rockettes and whisky breath, the bedtime stories that would take you to castles with swords and knights and knaves, the scratchy kiss good-night from the thick stubble on his nighttime face. I can still see him waiting for me, outside the train, smiling like a big kid waiting for a friend to come out to play.

The visits changed. One day my mother called me outside, to the porch where she shook a glass filled with ice and bourbon.

“Your father lost his job,” she said. I was 12, I couldn’t grasp the full meaning of what that meant, nor did she try to explain. But I knew that things had changed, just like when my brother died four years before. The wind was turning around again. I looked at my feet and turned away.

The next time I met my dad at Grand Central station, he took me to a bar. Everyone there knew him, just like when he took me to his office.

He ordered a drink, and took out his cigarettes, shaking the pack and offering me one.

“I know you smoke. You steal my cigarettes all the time, so I’m giving you one now.”

I took it and put it between my lips.

“Always wait for a man to give you a light,” he instructed me, as he pulled his lighter out of his jacket and flipped it open with a swift shake. He reached across the table and waited for me to draw smoke, then lit his own. I don’t remember if we ate.

There was no Radio City Music Hall that night. We got on a subway beneath Grand Central Station, sitting in the front, near the conductor, so we could see the tracks ahead, the stations appearing bleak and dirty as we stopped along the way, the doors sliding open to swallow the rancid air. Finally the subway reached the end, then jerked backwards, sending us back again. We stayed in our seats, watching the tracks disappear into the dark, not saying much.

Even after I met Jesus, at age 31, years after the subway ride and watching the daddy I loved slide into a deep pit of failure and despair, I still didn’t trust this new Father. I was grateful though. I knew He had rescued me from the same snare that caught my dad, I knew He had had somehow fixed what was broken. The mess that teachers and cops and therapists had just scratched their heads at, God reached down into my heart and in a flash – it was like new. But love? I doubted it.

My father died at age 56, when I was pregnant with my second son. He had been sober for seven years and in an awkward dance of reconciliation, we tried to build a bridge over years of my pain and his shame. I wrote letters because it was safer, describing the raw beauty of the lower Cape, and he lived within the fierce gales and the unrestrained sea. He liked that the gulls kept flying, even though they couldn’t get ahead. Cancer took him away from me for good in 1981.

Forgive your father, my new Father spoke to me. I argued a bit – we had made amends. He’s dead anyway.

Forgive your father, He insisted. So I did. And a strange thing happened. I could love again. My old dad, and my new Dad too.

This Father’s day, love your father if you can. And if you can’t, I suggest you meet the new One. And forgive.

Jesus answered, “I am the way and the truth and the life. No one comes to the Father except through me.” John 14:6 NIV

No one. That seems a little exclusive, I know, but you are all invited.

It’s funny – when I remember my dad, I remember the dad who loved me, the dad who sat through the Nutcracker Suite, smiling, who showed me off to his friends. He was a good dad. But I am even more grateful to my real Father, the one who gave me life, who poured His love out into my heart – a heart that quit love, quit hope, like those people a little girl on a train looked out at in Harlem 50 years ago. I couldn’t name it Despair then, but I would come to know it well.

Thank you, Father, for your love that is pure and boundless and never fails. And for Jesus, who made a way for me to find you. Your name is not Harold, it is Love. Perfect love.